From Lamine Yamal to Jony Ive to Digital Dali: Big Beautiful Bills and the New Choreography of Growth – Letter #30

“Art is the elimination of the unnecessary.” — Pablo Picasso

In a recent interview, Rio Ferdinand is asked one simple question: Who’s the best player in the world right now?

He doesn’t flinch.

No hesitation. No caveats. Just the name of a 17-year-old from Rocafonda, a gritty neighbourhood in Mataró, just outside Barcelona. The kind of place where futures are usually forged through grit, not grace. A kid who only recently finished school. Who’s already made over a hundred appearances for one of the most demanding clubs in world football. And who now wears the Spanish national shirt like it was stitched for him.

Ferdinand doesn’t compare him to Messi or Ronaldo. He dismisses the comparison entirely.

“He’s not like either of them. He’s Lamine Yamal.”

And then, almost reverently, he calls him something else: an artist.

Ferdinand says he had the pleasure of watching Yamal up close recently. What struck him wasn’t speed or power — it was rhythm. Yamal dictated the pace of the game like a conductor. Slow, fast, slow again — then gone. He didn’t force his way through the match; he flowed through it.

And perhaps the most remarkable part? His decisions. At an age when most forwards are desperate to score, eager to prove themselves, Yamal doesn’t panic. If a teammate is better positioned, he passes. If it’s his moment to shoot, he does. But he never forces it.

As Ferdinand put it, “It’s 50/50 — score or assist.” That balance is rare.

The artistry is not just in his craft — but in his judgment.

It’s a word we don’t use often enough in football. Or in business. Or in technology. But this week, it found its way into another headline.

The Artist’s Edge

No designer in the modern era is more synonymous with the word craft than Jony Ive. Not just because of what he made — like the iPhone, MacBook Air, and iMac — but because of how he made them: with care, with restraint, and with a quiet philosophy that beauty isn’t decorative. It’s essential.

This week, OpenAI announced it is acquiring io, the stealthy AI hardware firm Ive founded with a handful of Apple’s most respected engineers. The goal? To build a new family of devices for the AI-native age. Devices that, in the words of Sam Altman, will help people “create all sorts of wonderful things.”

We still don’t know what the first product is. But we know what it isn’t: not a phone, not a screen, and not something you’ll wear on your face. Ive has reportedly said this is the best work his team has ever done. Coming from the man behind the iPhone, that’s a manifesto.

Altman, for his part, calls it “the coolest piece of technology the world will have ever seen.” A high bar, but perhaps not an exaggeration. He believes it will ship faster than anything OpenAI has launched to date, which, given their pace, says a lot. OpenAI is already the fastest company in history to reach 100 million users — and the fastest to reach 400 million.

But the ambition runs deeper than timelines or hardware specs. Ive and Altman are trying to reshape the relationship between humans and machines. AI, in this vision, isn’t something you open. It’s something you live with. At the frontier of this technological revolution, it’s not enough for products to be powerful. They have to feel inevitable.

And that’s where the artist still matters most.

A New Kind of Creator

But what if the machine could become the artist?

At its annual I/O conference last week, Google unveiled Veo 3, an AI model capable of generating high-resolution, talking video. The realism is startling. Voices are synced to lips. Shadows fall naturally. The camera moves with cinematic confidence. If you didn’t know it was synthetic, you wouldn’t question it.

It’s the kind of technological leap that blurs a long-standing boundary. We’ve always thought of artists as human — those with judgment, taste, rhythm. But Veo raises an uncomfortable possibility: that some of those qualities might now be replicable. That AI might not just assist artists… it might become one.

Veo fits squarely into that shift. Generating video has long been one of the most computationally demanding tasks in AI. But that barrier is eroding. With tools like Veo and Flow — Google’s new video-editing platform — we’re entering a phase where AI can craft entire visual narratives, complete with dialogue, cinematography, and character movement.

And it’s not alone.

In Sweden, Stockholm’s Museum of Science and Technology unveiled The Impossible Statue — a stainless steel sculpture designed entirely by AI. It fused the styles of Michelangelo, Rodin, Kollwitz, Kotaro, and Savage into a single form never imagined by any one human. A digital artist without ego, drawing from five centuries of mastery.

In Slovenia, London-based architect Tim Fu revealed a design of the country’s Lake Bled church. The concept blended Gothic arches with Islamic tessellations — an architectural hallucination born not of hand sketches, but of AI-generated form finding. The result was alien and beautiful.

And in the UK, Ai-Da, the world’s first ultra-realistic humanoid robot artist, held exhibitions at the Venice Biennale and spoke before the UK’s House of Lords. Her works, drawn from real-time visual inputs and algorithmic processing, pose the very question she’s become famous for: Can a robot make art?

So, this is about authorship. Because the machine isn’t just rendering, it’s expressing. And whether that expression comes from lines of code or brushstrokes of oil, the idea of what counts as artistry is evolving by the day.

The Big and the Beautiful

You wouldn’t know it from Capitol Hill.

This week, the House narrowly passed President Trump’s “Big Beautiful Bill” — a 1,000-page mashup of tax cuts, entitlement rollbacks, and green energy reversals. It’s the legislative equivalent of shouting over the music: loud, urgent, and not particularly elegant.

The good news? In its new analysis, the Council of Economic Advisers finds the bill would add 4.2% to 5.2% to GDP in the short run.

But the headlines have focused elsewhere: roughly $4 trillion added to the national debt. Tax breaks tilted toward high-income families and seniors. A $1,000 “Trump account” for every newborn. An estate tax exemption bumped to $15 million. Standard deductions nudged higher.

What’s being taken away is louder still.

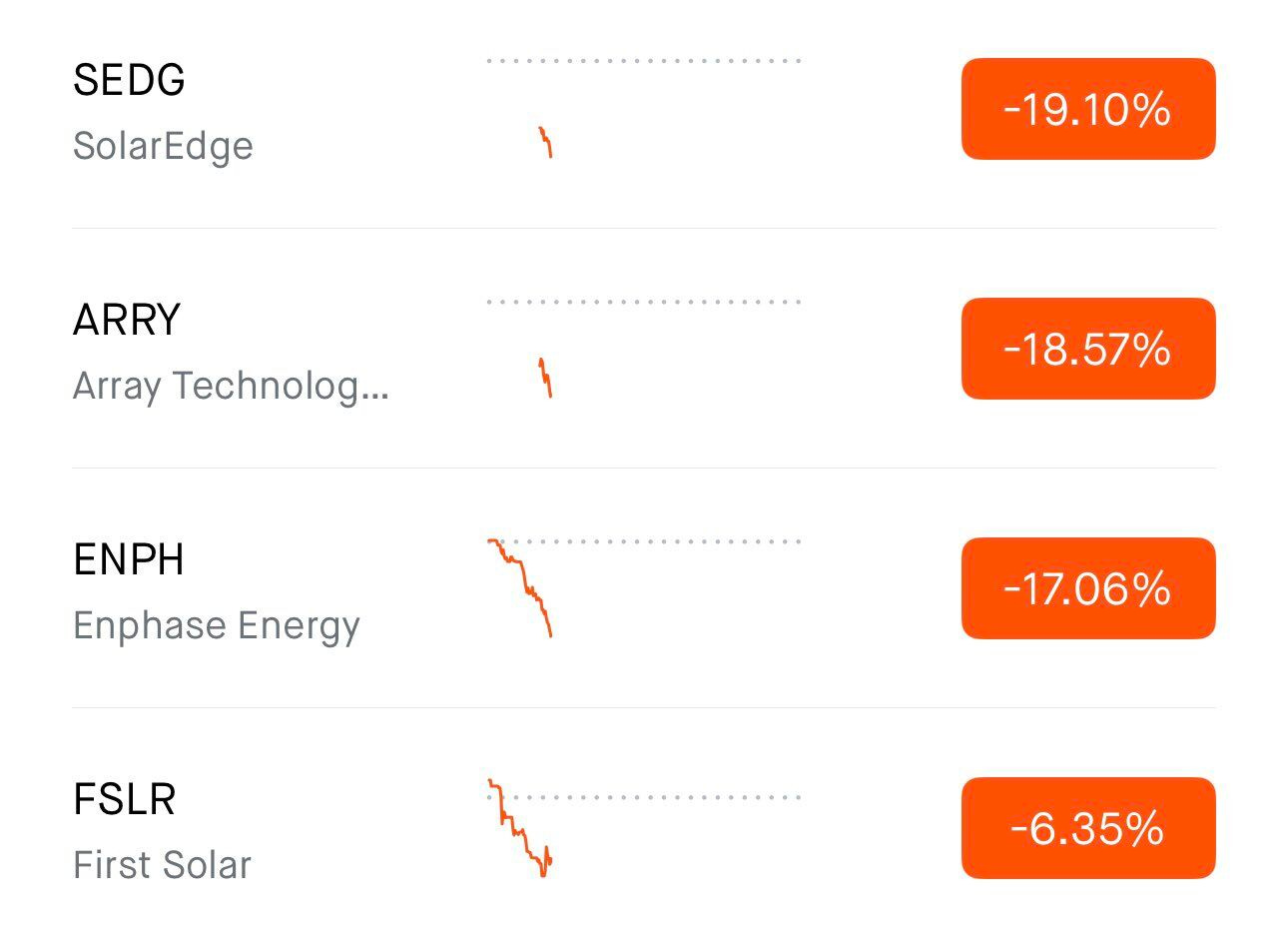

The bill guts nearly $700 billion from Medicaid — leaving millions at risk of losing healthcare. It slashes $267 billion from SNAP, the food stamp program. And it erases the $7,500 EV tax credit and other incentives central to Biden’s clean energy push. Solar stocks reacted like they’d looked directly into the sun.

For now, it’s a House-only affair. But the pressure is on. Trump wants it signed by July 4th. And while the bill scraped through on party lines, the Senate will be trickier. Some Republicans — Josh Hawley among them — are balking at the Medicaid cuts. Others are uneasy about a last-minute sweetener that raises SALT caps for wealthy states, just as Moody’s puts America’s creditworthiness on notice.

When the Bond Market Speaks

Bond markets have already begun marking up its costs.

There’s no austerity in this bill. What we do have are long-term obligations stacked on top of short-term giveaways. Even with some last-minute edits, the structure remains: more spending, less revenue, higher debt.

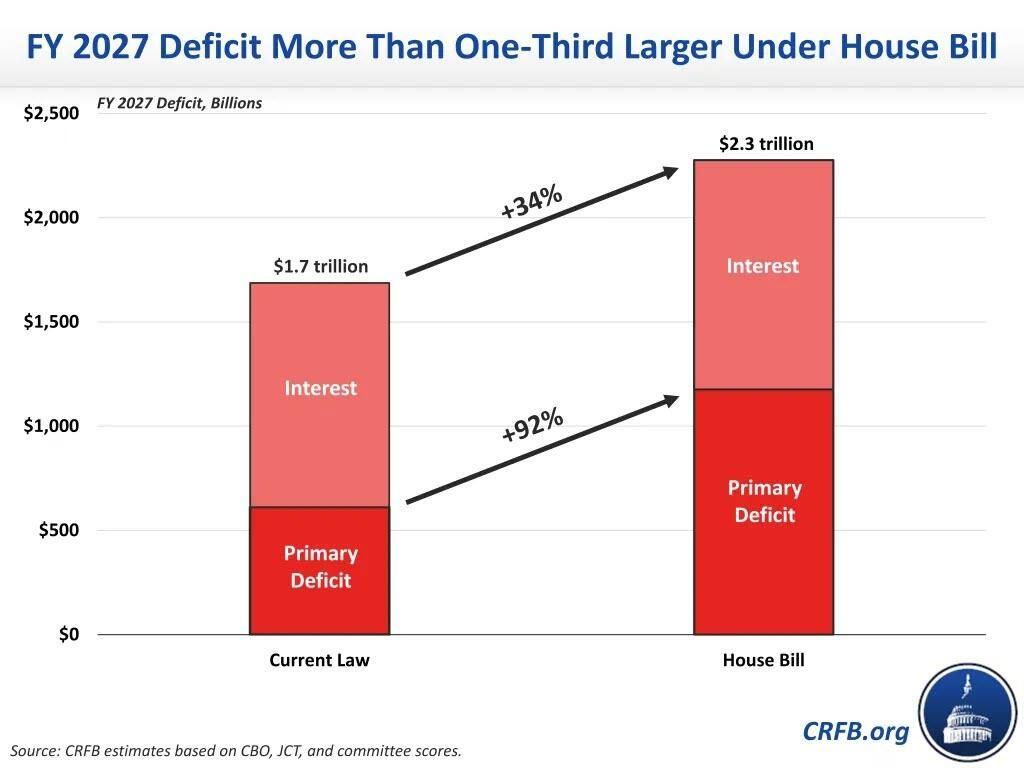

The CRFB estimates the bill would raise the FY2027 deficit by nearly $600 billion, pushing the total from $1.7 trillion to $2.3 trillion. That’s a one-third jump. The primary deficit — which excludes interest payments — would nearly double. All told, it estimates it could add $5 trillion to the $36 trillion national debt.

Yields have reacted. The 30-year Treasury breached 5% last week after a weak auction. The 10-year rose above 4.5%.

What does this mean? The CBO assumes average rates of 3.6% when projecting future debt service. But at 5.1%, the U.S. would spend an additional $525 billion a year on interest alone. That’s just to keep pace.

This is the feedback loop: higher deficits require more issuance. More issuance pushes up yields. Higher yields raise interest costs. Higher interest costs widen deficits again. Round and round we go.

Meanwhile, foreign buyers like Japan — once major backstops to Treasury demand — are managing their own bond market stresses.

If they become net sellers, yields may rise even further.

Gold and Bitcoin are both ticking up. Gold is up 27% year-to-date, while Bitcoin has recently caught up, rising 18% so far this year.

This matters because Washington has signaled austerity won’t be a policy decision. Outside of the MAGA Republicans, there seems to be bipartisan unwillingness to rein in spending. But the bond market isn’t waiting. The question now is how high long-term yields can go — or will be allowed to go. In April, the White House quietly paused its tariff rollout, a gesture that suggested someone was listening. The next move may require not just action, but choreography.

Choreographing the Bid

Enter Scott Bessent.

If markets are symphonies of fear and greed, the U.S. Treasury Secretary is stepping in as conductor. With $7 trillion in debt to refinance this year and liquidity thinning at the long end, Bessent knows jawboning won’t be enough. He needs buyers. Real ones. Soon.

And so begins the dance.

The first step is the banks. American banks already hold large amounts of Treasuries, but current rules limit how much more they can take on. The constraint is a regulation called the Supplementary Leverage Ratio, a Basel-era rule that caps total assets relative to capital.

That cap may soon be eased. Bessent has told Congress it is a top priority. Powell has echoed the urgency. And the three regulators that oversee the rule — the Fed, the FDIC, and the OCC — appear ready to act. Whether they lower the ratio or reinstate the pandemic-era exemption for Treasuries, the result is the same: more balance sheet capacity, more liquidity, and a stronger bid at the long end of the curve.

There are risks. Banks are still sitting on unrealised losses from the last bond rout. Buying more Treasuries means taking on duration risk just as the Fed remains data-dependent. But if banks start buying again, it could calm the market and reduce volatility.

The second step is newer, but potentially just as powerful.

Stablecoins, or dollar-pegged digital assets, already hold over $220 billion in Treasuries. That is more than Saudi Arabia. Bessent believes the number could grow significantly. A new stablecoin bill, expected to pass this year, would formalise the rules of issuance. Every new digital dollar would need to be backed by an actual dollar held in Treasuries.

This is regulatory clarity designed to unlock structural demand. Especially offshore, where stablecoins are used in places like Argentina, Turkey, Lebanon, and Nigeria to access the dollar system. If the bill passes, stablecoin growth could become a new and steady source of Treasury buying.

Together, these two moves may not fix the deficit problem. But they could address the more immediate challenge: thin liquidity and high bond yields. If it works, Bessent will have plugged a gap. He’ll have restored rhythm (and flow).

Growth Is the Way Out

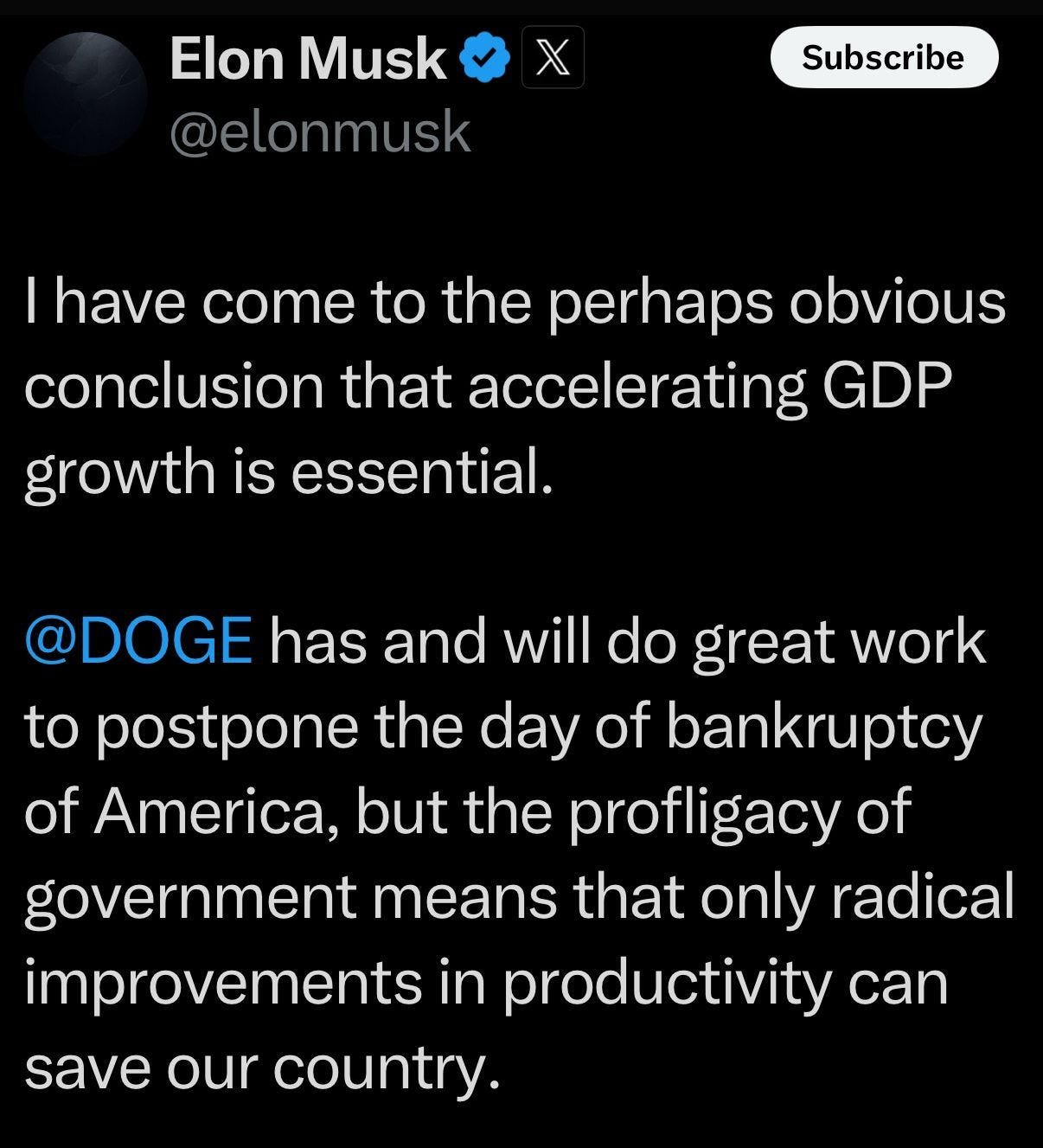

One of the more consequential tweets this weekend came from Elon Musk. It wasn’t about AI, or Mars, or the latest in autonomous driving. It was about debt.

Not the existence of it, but the path forward.

The takeaway: America is going to struggle to stop spending. The DOGE initiative, despite its intent, delivered only modest savings — around $150 billion, or less than three days of deficit spending. The machinery simply won’t cut itself.

So the strategy has shifted. The focus is now on growth.

As Scott Bessent put it last week, “What’s important is that the economy grows faster than the debt.” That’s now the organising principle. It marks a structural turn toward nominal GDP as the policy anchor.

And there’s much reason for optimism. If the U.S. can unshackle its most productive technologies — in AI, robotics, industrial automation, and blockchain — growth can compound. Deregulation matters. So does capacity investment. A nominal target doesn’t preclude real progress.

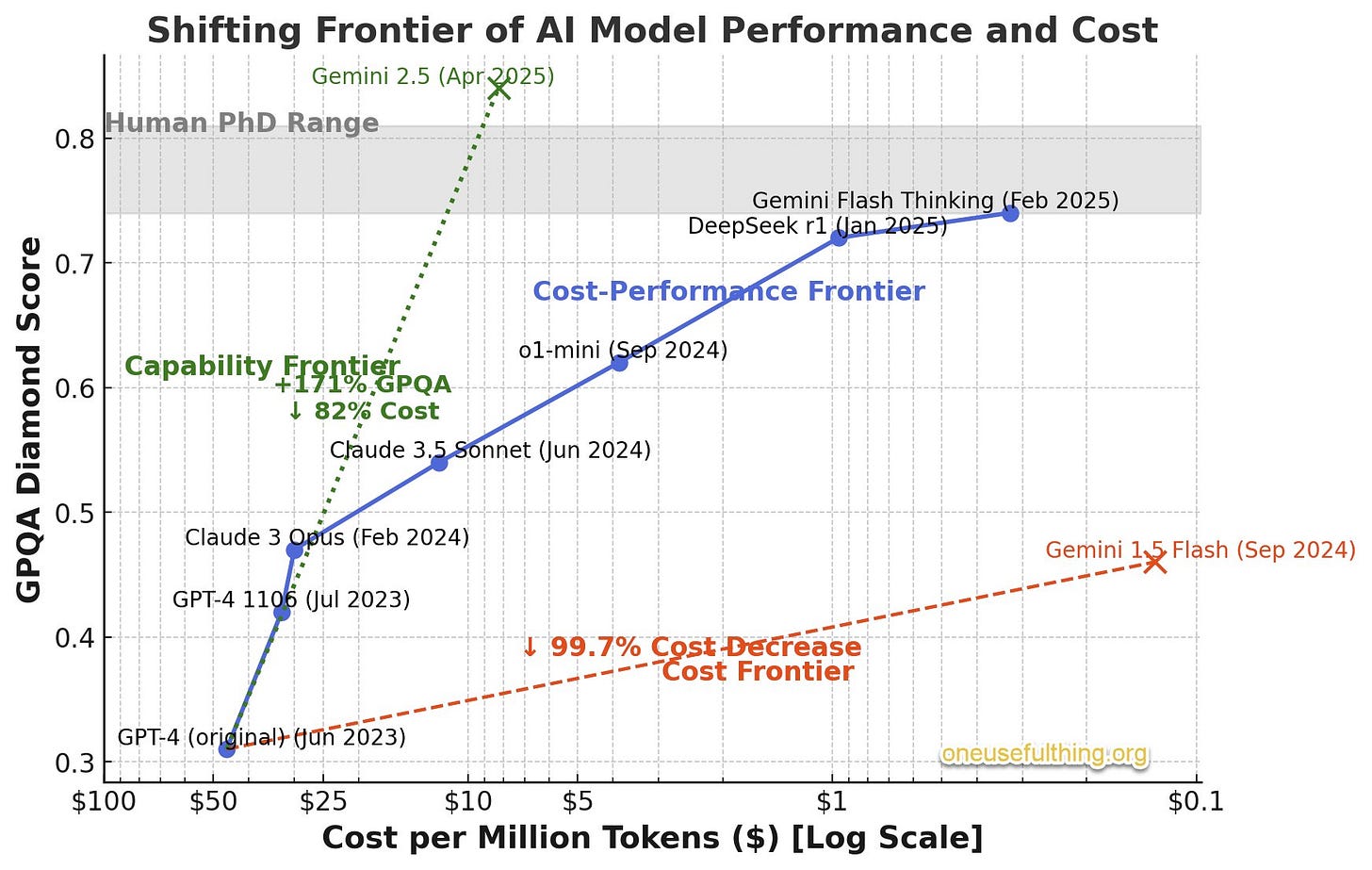

AI is now being embedded directly into business processes — not just for experimentation, but to rewire entire workflows. From copilots to autonomous agents, the focus is shifting to enterprise-wide deployment. Cost curves are falling. Productivity is rising.

Robotics and industrial automation are hitting escape velocity. Across logistics, manufacturing, and construction, the use of intelligent machines is turning physical labour into software-scalable processes. This is no longer just about efficiency. It’s about enabling entirely new forms of output.

What matters now is speed. Policymakers are responding. But we also need to understand real-world constraints. Let’s spend a moment on perhaps the biggest of these: energy.

If growth is the goal, energy is the throttle. And right now, it’s partially stuck. Years of underinvestment, geopolitical fragmentation, and regulatory caution have created a system that struggles to scale. The U.S. remains energy-rich, but not energy-agile.

AI needs power. Manufacturing needs metals. Data centres need cooling. Yet interconnection queues for new energy projects stretch for years, and permitting remains a morass.

This is why the energy transition can’t just be clean — it has to be fast. The U.S. must unlock gigawatt-scale projects across renewables, nuclear, and next-gen fossil infrastructure. That means policy coordination, not just innovation. It means treating energy capacity as a national asset. President Trump’s nuclear executive order last week is a pragmatic signal in the right direction. This new industrial policy will be defined by energy pragmatism.

In a world where the fiscal engine is running hot and real rates are positive, energy is the limiting reagent.

Fix that, and the rest — AI, automation, onshoring — can accelerate.

Feel the pulse, stay ahead.

Rahul Bhushan.