Tales of Krampus, Fed Flip-Flops, and the Folly of Fixations – Letter #15

“The more you try to control something, the more it controls you.” – Frank Herbert

This will be my last newsletter of the year. Thank you for your continued readership and thoughtful engagement—it has been a privilege to share these insights with you. I’ll return to writing on either January 6th or 13th—data dependent 😊. Wishing you a joyful holiday season and a prosperous start to 2025!

The image of Christmas in the West is a familiar one: twinkling lights, stockings hung by the fire, and the promise of gifts from a jolly, red-suited Santa. It’s a season of generosity and celebration, where the spirit of goodwill seems to wrap itself around every home.

But not everywhere celebrates Christmas in quite the same way. In parts of Eastern Europe, St. Nicholas—the 4th-century saint who inspired the modern Santa Claus—is not alone in his yuletide duties. He is accompanied by a creepy counterpart: Krampus, a half-goat, half-demon figure from Central and Eastern European folklore who punishes children who misbehave. His origins are murky, though many believe he has roots in pagan winter solstice mythology. Even his name, derived from the German word Krampen, means “claw”…

I first heard the story of Krampus during a stay in Prague in 1997. In some versions of the tale, his punishments are pretty intense—he carries the most reckless children away to his lair, chains rattling in the dark. Imagine trying to set that grim specter to music in a Christmas carol 😅.

This interplay between reward and retribution feels especially relevant as we consider financial markets today. Investors have spent much of the year with their hopes pinned on gifts from the Federal Reserve: lower interest rates, dovish policy, and a path of least resistance.

Yet, instead of receiving comforts, we’ve sometimes been met with Krampus, jolting markets out of their complacency. This has compelled markets to confront an inconvenient truth: the Fed was never intent on establishing a clear or consistent framework. Instead, it persists in being "data-dependent", adjusting its course in response to the unpredictable tides of economic indicators.

This week, we analyse the Fed’s hawkish cut, the market’s volatile reaction, and how data dependency shapes both policy and investor behaviour.

Let’s dive in.

Flip-Flops

Last week, the Federal Reserve (“Fed”) delivered what it described as a “hawkish cut”. On the surface, the idea seems contradictory: a 25 bps reduction in interest rates, typically a dovish signal, was paired with guidance that painted a far less accommodative picture for the future. The Fed indicated fewer rate cuts in 2025 and a higher terminal rate than previously anticipated.

The core question driving market debate is why the Fed acted this way. Has it shifted its approach in anticipation of major policy changes from a new administration (e.g. higher tariffs, more tax cuts, a reduction in the labour force due to the repatriation of illegal immigrants)? In November, Chair Powell stated that the Fed does not speculate on incoming government policy. Yet some argue the Fed’s shift reflects an attempt to “pre-position” for these potential changes.

Others dismiss this interpretation, insisting the pivot is about the persistence of sticky inflation. Data, they argue, has forced the Fed to act. As with many debates about Fed policy, all we know is that this marks yet another instance of the Fed’s tendency to flip-flop.

Consider the past four meetings:

In late July, the Fed downplayed the need for rate cuts.

By the next meeting in September, it delivered a jumbo 50 bps cut—far more aggressive than expected.

In November, the Fed projected a steady series of 25 bps reductions.

And now, in December, a hawkish turn…

Market Fallout

Markets wasted no time reacting. The 10-year Treasury yield’s climb past 4.4% marks the steepest rise since 2013’s taper tantrum—a move that left the markets rattled. Meanwhile, the VIX, Wall Street’s “fear index”, nearly doubled in a single day, reminding investors just how fragile the calm can be.

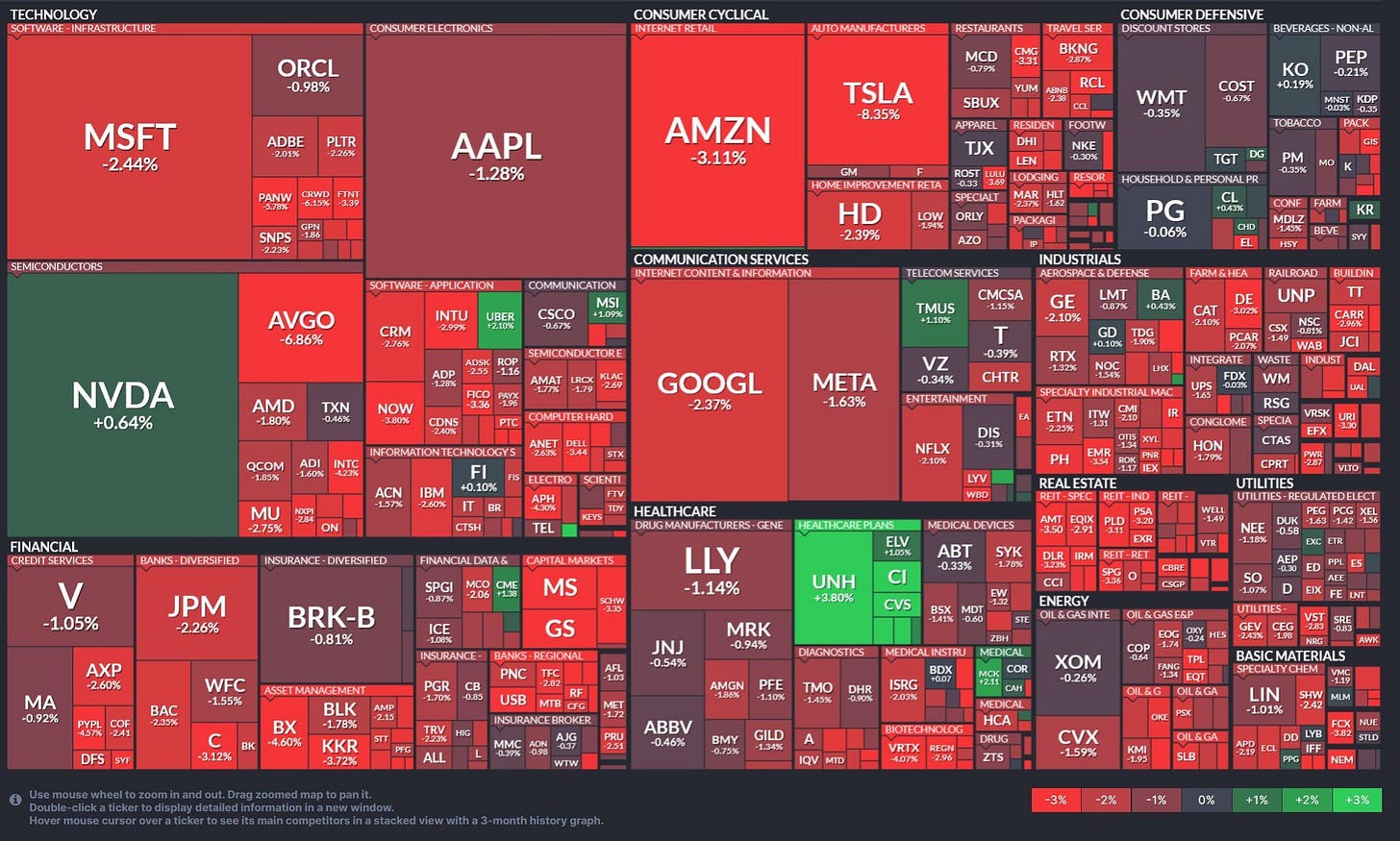

The S&P 500 dropped almost -3%, the worst “FOMC decision day” performance since 2001, and the worst after a Fed meeting since the pandemic.

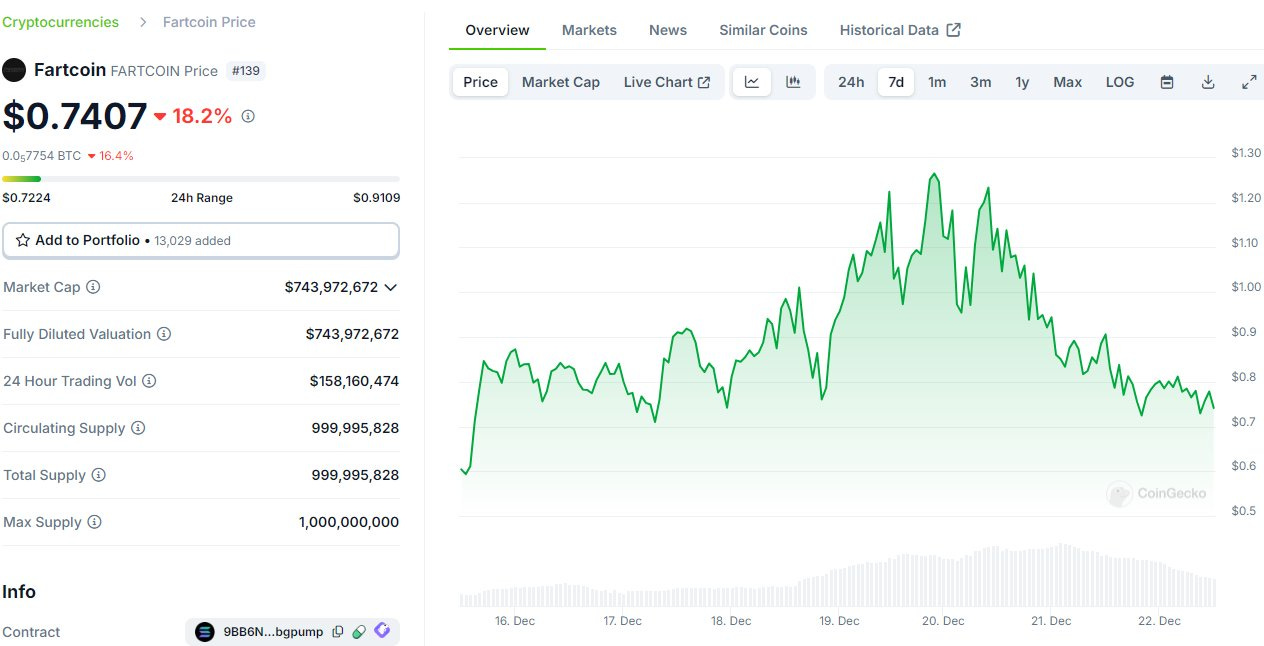

Even the market’s newest assets, despite hitting $1 billion dollar market capitalisation last week, couldn’t hold on (in?) its gains.

It was finally Friday’s PCE release that managed to bring some calm to the markets. The report showed that November’s PCE inflation—the Fed’s preferred measure—rose to 2.4%, just shy of expectations at 2.5%. Core PCE inflation came in at 2.8%, slightly below the forecasted 2.9%. These better-than-expected “dovish” numbers offered a measure of relief, restoring a bit of holiday cheer.

2025

The bond market is currently anticipating only a single 25 bps rate cut from the Fed for the entirety of 2025, a sharp contrast to the six (!!) 25 bps cuts that were expected back in September.

Treasury Yields

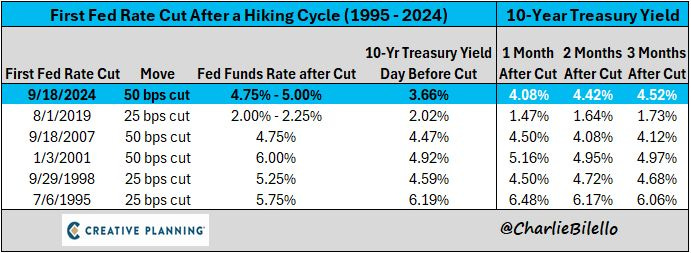

Meanwhile, the bond market is telling its own story. It’s been three months since the Fed first cut rates, yet the 10-year Treasury yield has climbed ~80 bps, rising from 3.6% to 4.4% (currently). This behaviour sharply contrasts with previous rate-cutting cycles, where the 10-year yield typically moved lower or stayed relatively stable.

This divergence raises an uncomfortable question: what does the move in yields say about the Federal Reserve’s credibility? The Fed’s decisions reflect a recurring absence of long-term strategy.

And this obsession with data dependency reminds me of a different kind of fixation I came across this week.

Darwin Award

On December 14th, Colorado native Will Duffy led an expedition to Antarctica to settle the age-old debate about the Earth’s shape. The group included four Flat Earthers and four Globe Earthers (or, as I like to call them, graduates of the educational system). Flat Earthers have long believed that Antarctica is not a continent but a 150-foot-tall ice wall encircling all other continents and oceans, guarded by NASA employees to prevent curious citizens from climbing over and falling off the edge.

The expedition disproved at least some of these ideas 😊. Duffy showed the group 24 hours of sunlight in Antarctica—a phenomenon only possible due to the tilt of the spherical Earth. Flat Earth influencer Jeran Campanella was finally convinced, admitting, “Sometimes you are wrong in life.”

But not everyone was swayed. Austin Whitsitt, another member of the group, dismissed the evidence. “I don’t think it falsifies plane earth, I don’t think it proves a globe,” he said. “I think it’s a singular data point.”

It turns out clinging to data dependency isn’t just a Fed thing— it’s a universal folly, even at the ends of the Earth.

Feel the pulse, stay ahead.

Rahul Bhushan.

Great read - happy holidays!